SUZANNE BING

SUZANNE BING, an established actor, was instrumental in reopening the Vieux Colombier School after WWI. Originally founded by Jacques Copeau in 1913, it closed during the war, reopened on a small scale in 1920, and was fully operational for the 1921-22 academic year. Bing was a teacher and, effectively, assistant principal. She had taught children and adults (the latter at the Sorbonne). Bing and Copeau envisaged actors as primary creators, not merely interpreters of a playwright’s text. To this end, she found creative ways to forge a new teaching praxis. Copeau would read La Fontaine’s fables and then ask students to improvise animal behaviour; Bing took them to the zoo to observe how animals moved. She translated Shakespeare into French and introduced her students to Noh theatre, a continuing Japanese art from the fourteenth century. Slow and highly stylised, she studied Noh to mine how actors could embody stage authority and presence. Masks could transform ordinary actors into extraordinary characters. Stillness was powerful. In these ways, she developed studio tools to equip actors for a new age.

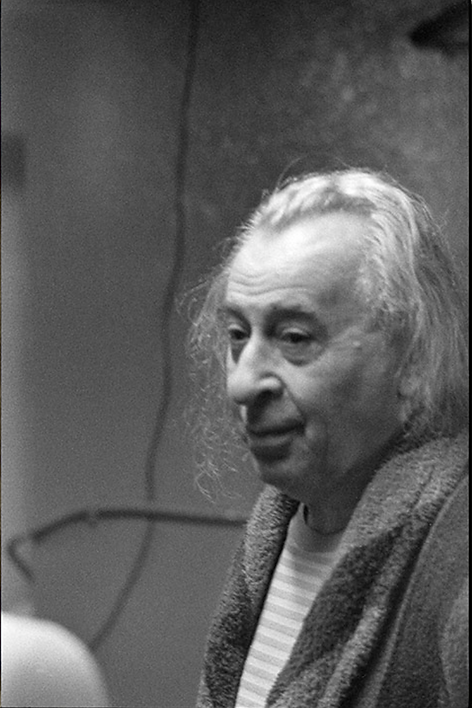

ETIENNE DECROUX

ETIENNE DECROUX joined L’École du Vieux Colombier as a student of diction in the Autumn of 1923. After seeing students in movement classes he found his life’s calling. Ten years later, with professional colleagues, he furthered his thinking on movement for the actor. In 1963 he published the first edition of “Words on Mime”. Today Decroux is universally considered the father of modern mime.

Decroux elevated the actor’s body into an instrument for art. Artforms have techniques that underscore artmaking: music’s scales underpin melody; ballet’s barre enables dance. Each part is distinct and deeply interwoven. Decroux’s Corporeal Theatre (Mime Corporel) was no different. Mobile Statuary embodies the fundamentals of his technique: the actor learns to master articulation of straight and curved lines, rhythms including immobility, shifts of weight, and varying of their centre of gravity. The more theatrical element was the study of characters: how they work and walk. If, in Bach, scale and melody become one, so too in Corporeal Theatre: abstract expression and recognisable characters are intertwined.

One point of this art form was to reveal deep humanity in any character. Another was to show intent: before uttering a word, the actor reveals the mind of their character. The audience senses this and experiences that moment as physically and spiritually potent.

Photo@Christian Mattis Schmocker, Bern Switzerland. www.mattis.ch

GEORGE HÉBERT

In 1921 Hébert joined the academic staff of l’École du Vieux Colombier to teach Physical Education. Whilst in the French Navy he developed the exercise regime known as Hébertism based on a philosophy of altruism: être fort pour être utile (be strong to be useful for others). He left the Navy post WWI and developed physical culture programs for men, for women, and for children because, he insisted, exercise was both a good and a right for ordinary citizens. He published several books. Hébert distanced himself from his training method when the French government made it a core requirement for youth in French schools.